In debates about film curatorship, it is common to return to the Latin origin of the word, curare, to reaffirm the purpose of the curator’s work: curating as caring or looking after; curating as zeal. The role of this profession in cinema is relatively contemporary, as are the debates and formulations by film scholars or programmers on the subject. These conversations are not born out of traditional film culture, which sees curatorship as a practice legitimized by traditional cinephilia (that is to say, the European film culture that arose during the second half of the twentieth century, developed around the centrality of the idea of authorship), but instead out of conversations among those who historically were marginalized by hegemonic cinema.1 Only in recent years has the field attempted to demystify the erudition required to be a film curator and produce reflections that openly consider curatorial activities as indisputable exercises of power.

Yet even when considering curatorial activity as a gesture of care, and thus combatting these dynamics, it is necessary to ask whom this work benefits. In the history of film festivals, curatorial choices often represent trauma much more than care, particularly for nonhegemonic filmmakers and audiences who are mainly not of European descent or male. This sentiment rings especially true regarding cinema in Brazil—the place where I was born, and where I live and work today.

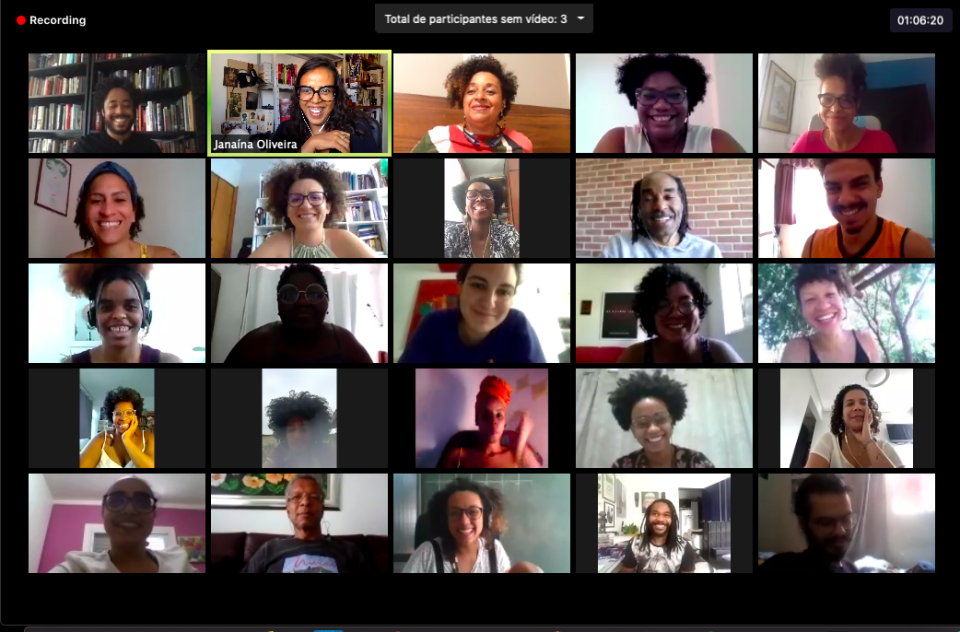

Until recently, mainstream Brazilian cinema and its big festivals had long maintained the racism and discrimination that unfortunately mark Brazilian society. My activities as a curator stem from a deep dissatisfaction with the negative, or absent, repertoire of images featuring Black populations on screens. These sentiments are echoed by most of my Black curatorial colleagues with whom I have spoken through Politics of the Gaze, a series of conversations held over the last two years, dedicated to exploring curatorial practices among Black curators from different parts of Brazil and around the world. The series happens during the annual Encontro de Cinema Negro Zózimo Bulbul: Brasil, África, e Caribe (Zózimo Bulbul Black Film Festival: Brazil, Africa, and the Caribbean).

Created in 2007 by Zózimo Bulbul, then already considered the pioneer of Black cinema in Brazil, the festival became the most important exhibition for Black films in Latin America.2 The Encontro was born in Bulbul’s late seventies as a platform for African and African-descended films. It was also founded to ensure that Black Brazilian films had a place to be seen, reflected upon, and embraced by local audiences. After Bulbul died in 2013, the festival was curated by filmmaker Joelzito Araújo. In 2017, Araújo invited me to share this role with him, a position I have held since then.3 The continuing of Bulbul’s legacy of curatorship is defined by gestures of embracing.4 He carved a path for curatorial processes in Brazil, particularly for them to stop being synonymous with invisibility or misrepresentation, which Black people in the country had come to expect.

My career trajectory was born out of my desire to contribute to ending this invisibility in the field through collaboration, undeniably inspired by Bulbul’s initiatives. Thus, curating is a twofold activity for me. Firstly, it is a form of intervention, as I join Bulbul in his aspiration to make exhibition spaces less exclusive so that films from different places, perspectives, and positionalities can be seen, appreciated, and discussed. Simultaneously, it is an attempt to move beyond the trauma and healing lexicon and think of curating as a gesture of offering.5 This is literal in the sense that everyone can take what they want from the experience being proposed by the curatorial project, because its main gesture is to create opportunities for access and fruition. This is presented in each film session, in each debate, and each training activity that may be part of the program, emphasizing the relational possibilities and the dialogues presented on each occasion.

My activities as a curator stem from a deep dissatisfaction with the negative, or absent, repertoire of images featuring Black populations on screens.

An example of these dynamics are the editions of the Encontro that I have programmed since 2018. Following the approach proposed by Bulbul, the festival remains the main national platform for Black films; in the most recent edition, seventy Afro-Brazilian films were shown (sixty-three shorts and seven feature films) in just ten days.6 It is always a challenge to organize the festival in a way that sufficiently probes the panorama of contemporary Black film production, always bearing in mind the country’s continental extension as well as the multiplicity of cinematic genres that are now being explored by the filmmakers. This ensures that the films can be experienced as art objects, rather than presumptuous reflections of what is assumed to be Black life or of what traditionally is expected of “a Black film.” My intention as a curator has increasingly been to progress the field of programming through discussions that foster reflection and expand aesthetic paths beyond the axes of representation and representativeness.7