I remember first hearing of August Wilson when Fences was on Broadway. As far as I can recall, it’s one of the first Black plays that had its own television commercial, and each time it aired the announcer would say something like “Come see Fences by August Wilson.” I remember thinking that August was a funny name for a woman. I, of course, later learned that he was a man and a revered playwright, but I have always known more about the work of August Wilson than the man himself. The PBS-produced documentary by Sam Pollard, The Ground on Which I Stand, successfully rounds out the story of one of the greatest American playwrights of the 20th century.

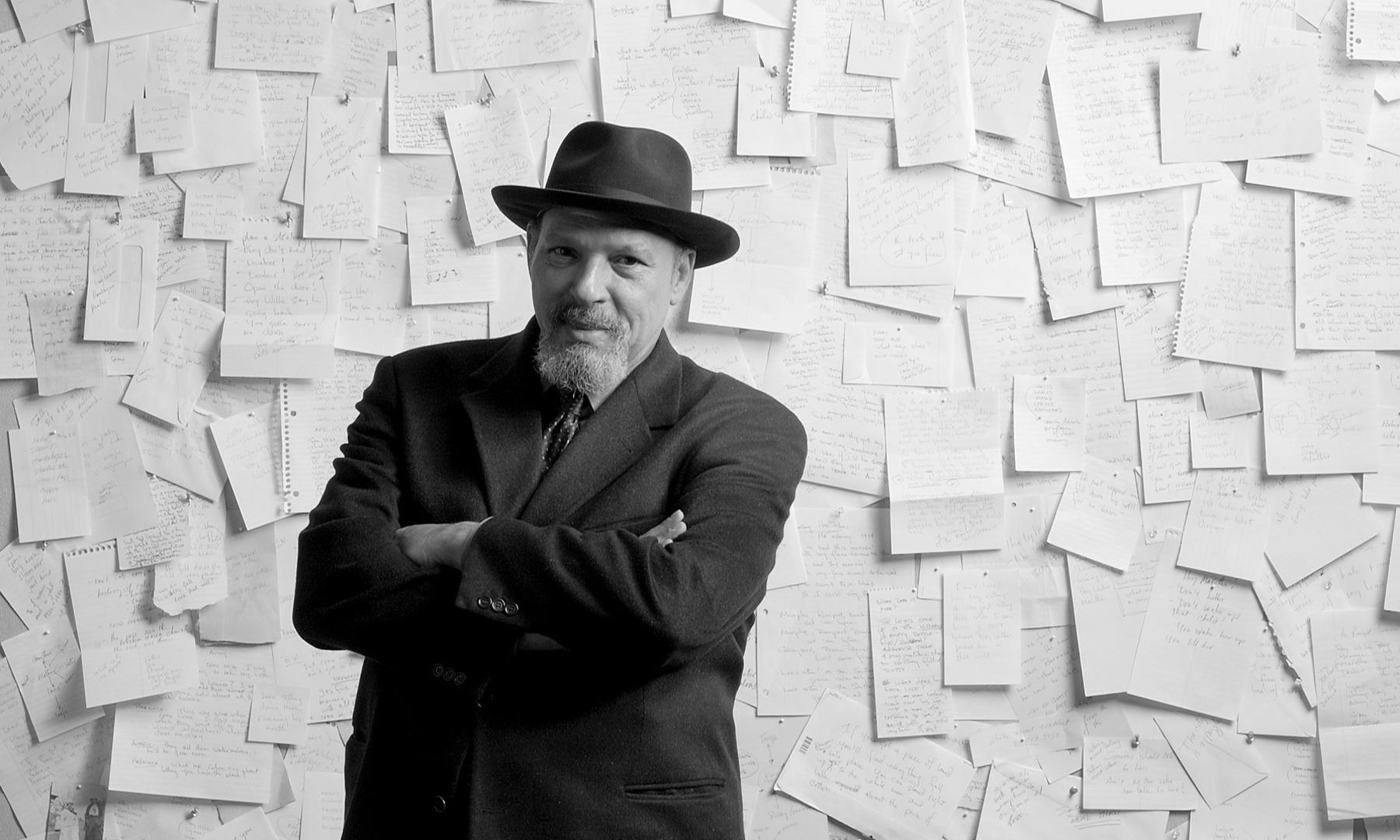

August Wilson, Yale Repertory Theatre

The theater was a big deal in my house growing up. My mother took me to my first Broadway play when I was in elementary school, and when she and her friends went out to the theater it was an event—especially when it was a Black play.

Using live script readings, clips from productions, interviews from the people whose lives he impacted the most, and rare and never-before-seen footage from August Wilson himself, this first documentary about the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner does a spectacular job of bringing the viewer inside his life and mind. This film gives us access in a way that documentaries with deceased central characters often cannot. Because we hear much of the story told in Wilson’s own voice, it adds a layer of authenticity that is sometimes missing when a filmmaker is forced to string together bits and pieces of someone’s life through the eyes of individuals with myriad perspectives.

There isn’t a moment wasted in the film. The story starts at the beginning of Wilson’s life to draw a roadmap of how he got to the place where we all met him. The childhood memories of his impoverished beginnings and subsequent self-education made it clear how he was able to capture the essence of the Black experience and paint it for us in ways that evoked a sense of familiarity and a curiosity at the same time. An autodidact, Wilson masterfully captured the spirit of the men and women he encountered on the streets of Pittsburgh; he shaped them into stories and characters that left an indelible imprint on American hearts and minds.

Everything he wrote added layers of humanity, complexity, and vulnerability to his characters—Black characters who might otherwise be viewed through a singular lens.

In the opening of the film, Pollard uses powerful quotes to help vocalize that imprint:

He finds poetry in everyday life and sings to it…

He wrote the frustration and glory of being Black…

He helps us remember who we are…

Wilson was unapologetically Black way before that saying became a thing. It is clear from the film how the Black Power Movement influenced him and ushered him into the Black Arts Movement. His commitment to Black struggle was embedded in all of his work as a writer and theater advocate. Everything he wrote added layers of humanity, complexity, and vulnerability to his characters—Black characters who might otherwise be viewed through a singular lens.

Without once saying it, Pollard portrays Wilson in a way that we don’t often see Black creatives portrayed: as a genius. Much like other prolific Black storytellers, Wilson and those closest to him talk about how he crafted his stories by capturing random bits of dialogue that happened in his head. He let the characters speak and followed them wherever they led.

From Viola Davis’s Tonya in King Hedley III to Charles S. Dutton’s iconic Boy Willie in The Piano Lesson, some of Black theater’s most memorable characters and performances have come from August Wilson productions. In the documentary these actors share stories about the process of working with Wilson and how the work itself impacted them. The viewer gets a greater sense of the imprint Wilson left, not just on American theater but on Black arts in general.